Mr Hill’s Big Picture, John Fowler, Saint Andrew Press, pbk, 216 pp, £9.99.

Mr Hill’s Big Picture, John Fowler, Saint Andrew Press, pbk, 216 pp, £9.99.

A whole book about a single picture seems a bit extravagant, but then it is no ordinary picture. The vast oil painting of the General Assembly of 1843 remains a remarkable memento of that great occasion, a reminder of the massive scale, and tremendous importance of the Disruption.

A shaft of sunlight from above illuminates Thomas Chalmers in the Moderator’s chair, and Dr Patrick MacFarlane, as he signs away the richest living in Scotland for a Free Church minister’s stipend. Assembled around them are 450 individual portraits, each one an exact and careful likeness, of the founding ministers, elders and key supporters of the Free Church of Scotland, together forming an extraordinary visual representation of the great Assembly. Above the painting are inscribed the words: “Unto the upright there ariseth light in the darkness”.

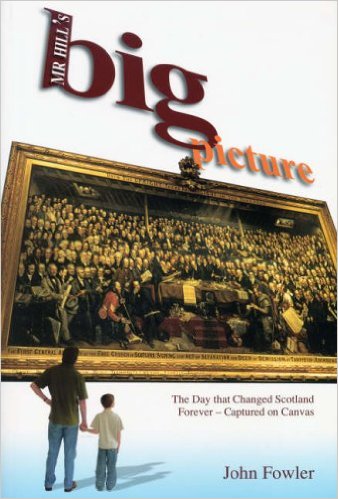

The cover of this book is superb – the great painting displayed as on an invisible wall, while in the foreground, a father and son in modern dress gaze upon the scene. The sub-title says it all: “The day that changed Scotland forever – captured on canvas”.

The book is about more than the painting, of course, and encompasses a narrative of the whole Disruption controversy, an account of the leading figures, and especially the genesis of the great picture. Written in a fresh and easy style, by professional journalist John Fowler, the volume introduces us to the artist, David Octavius Hill, and his photographer, Robert Adamson. It is fascinating to read evidence that these men, Free Church members both, were indeed committed Christians.

Hill devoted 23 years to the massive endeavor of the Disruption painting, working on it from 1843 onwards, until its eventual completion in 1866. The technical challenge was vast: to get each individual, some of them ministering in remote corners of the British Isles, and indeed of the whole world, to sit individually for portraits would be out of the question. Therefore, the pioneering art of photography was harnessed to capture the necessary likenesses.

Fowler gives fascinating insight into the difficulty of early photography, with mechanical supports sometimes necessary to hold the posers in place for the long exposure times, and many hours of patient chemical washing required for the development of each image. These primitive calotypes, as they were called, of founding Free Church Fathers, such as Chalmers, are among the earliest photographic portraits taken, and the collection is quite as interesting as the eventual painting itself.

Over time, the gathering grew and grew as more and yet more faces were added. Hill’s determination to make his painting a definitive record of the early Free Church led him to add many faces of men obliged to be absent from the first General Assembly in Tanfield Hall, including at least one belated commissioner who sat on in the Established Church Assembly that day, and only later cast in his lot with the Free Church. Apparently, Mrs Hill became so impatient with the slow progress that she began rising early in the morning to fill in shirt-fronts and cuffs before her husband was in his studio!

The end result is a gathering quite overwhelming, and such is the size and detail of the work that reproduction is difficult. A high-resolution rendering is included as a fold-out inside the rear cover of the volume, but even that cannot do justice to the vast picture, and individual faces remain somewhat blurred. In truth, the painting is not a great success as a piece of art, so overwhelming is the sheer number of individuals portrayed. One genuinely cannot see the wood for the trees in looking at this painting, and the significance of the occasion is somewhat lost. George Harvey’s Quitting the Manse is a far more successful visualization of the sacrifice of the Disruption fathers.

In his narrative, Fowler wishes to bring his readers back to the Disruption; but in this, he does not wholly succeed either. Like many secular authors, he doesn’t quite get it. He does not understand what the Headship of Christ means, nor does he appreciate that the difference between the people’s choice and the patron’s appointee was usually the difference between a fervent Gospel preacher, a winner of souls, and a stipend-seeking placeholder. He understands the Disruption as a movement of democratic assertion, not as the outpouring of Evangelical conviction and commitment it truly was. In giving subsequent history, the usual sneers about “Wee Frees” are cheerfully included – does anyone still talk about “Wee Frees” nowadays except supercilious journalists? No understanding is shown of the rapid defection of the next generation of Free Churchmen from commitment to confessional truth.

Fowler is also careless in details, especially in misspelling so many names one almost wonders if he is testing us: “Horatio Bonnar”, “Merle D’Aubignon”, “Richard Buchanan”, and so forth. Furthermore, despite telling us much about the calotypes, he fails to include a single reproduction of them in the book, though thankfully Google searches will obtain most of them. Worst of all, despite including the reproduction of the painting itself, he fails to include the key. This is a staggering omission – a whole book about a painting, and it does not even name everyone in it?!

But this book is genuinely recommended. It is a fresh and lively work, easily read, that brings alive again the events of the Disruption. For any who would like a fresh reminder of how we came to be the FREE Church, and to be introduced to the painting that commemorates that, a quick read of Mr Hill’s Big Picture would be just the answer.

Leave a Reply