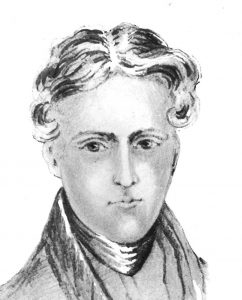

Rev Alasdair J Macleod

Rev Alasdair J Macleod

Robert Murray McCheyne died a young man, yet his achievements were broad, and his significance is consequently substantial and diverse. The focus for this paper is the ‘Life and Sermons’, and therefore I will focus particularly on McCheyne the preacher. His importance in this area is more than sufficient to justify serious and sustained attention, as I will particularly aim to demonstrate, especially to those unfamiliar with the quality of McCheyne’s sermons. Indeed, I aim to show that he is one of the great lights of the nineteenth-century pulpit, and consequently one with plenty to teach the preachers of today.

With such a focus, inevitably some areas of interest from McCheyne’s life must be left for other occasions. In particular, it will not be possible to address at any length McCheyne the pastor and personal evangelist; the man of prayer; the lover of the Jews and co-founder of what later became Christian Witness to Israel; the explorer of the Middle East and co-pioneer of the Scottish mission to Budapest; or the one who experienced blessed revival on his return to Dundee. All would make stirring papers; but right now, let us focus above all on McCheyne the preacher of the Word of God.

In structure: I will briefly introduce my approach to McCheyne in the context of Christian biography; then (I) outline the life, especially as it relates to his initial development as a preacher; (II) conduct a general analysis of McCheyne the preacher on the basis of the evidence we have in the extant published sermons; and (III) draw out some key practical lessons for modern preachers to apply from McCheyne’s example. I will conclude by outlining the best current literature available on McCheyne. Note that I will draw most of my examples for this paper from the three recent volumes of hitherto unpublished material printed by the Banner of Truth, Old Testament Sermons, New Testament Sermons and Sermons on Hebrews, especially the first two of these, for reasons that will become clear as we proceed.

Introduction: McCheyne and Christian Biography

Hagiography is the curse of Christian biography, and nowhere more evidently than in the posthumous study of Robert Murray McCheyne. He towers before us now, in the mind’s eye, the powerfully zealous, wonderfully blessed, startlingly young minister of St Peters, Dundee, ever immortalised as a Presbyterian Saint. The frequent quotations we hear in sermons are invariably prefaced: ‘the great…’, ‘the holy…’, ‘the saintly Murray McCheyne’, and with good reason. McCheyne’s biography is a stirring, humbling record of Christian endeavour and achievement; a minister who did more in 29 short years of life than most who double or treble that lifespan. The diary extracts reveal even in private life a burning passion for holiness, an earnest longing to win souls, a passion for the glory of Christ. Farther from the stipend-lifting Moderate it would be hard to travel.

But the problem with hagiography is the application. Too often wonder becomes the end point, and we are left like the Romanist giving credit to the person, building our pantheon of small gods who can and do only serve to divert our praise from the one Perfect Man, the Lord Jesus. A subject portrayed at length without identifiable fault borders on blasphemy in attributing to man what is true only of Christ. In terms of promoting emulation, which is surely the point of Christian biography, such leads only to despair. How can I ‘be holy like McCheyne’, when all I read of McCheyne is holiness, when in fact the ‘McCheyne’ we know is a fictional creation, gently sanitised by his loving biographer from the taint of everyday sin?

Two solutions present themselves. First, I intend to take my life in my hands, and diverge from virtually every biographer of McCheyne in drawing a couple of negative as well as some positive lessons from McCheyne’s life-work as a preacher of the Gospel. And second, in drawing positive lessons, let us remember McCheyne’s own remark on a saint of an earlier generation, Jonathan Edwards: ‘How feeble does my spark of Christianity appear beside such a sun! But even his was a borrowed light, and the same source is still open to enlighten me’ (Memoirs, 16). Therefore let us attribute the qualities we admire in McCheyne to the sanctification of the Spirit, and pray for the same. Pray, if I may say so, even to want to love the souls of men as much as McCheyne, and pre-eminently, to love Christ Himself.

- The Life of McCheyne: The Development of a Preacher

McCheyne was born in 1813 into a prosperous middle-class family in the New Town area of Edinburgh. His father, Adam, was a Writer to the Signet, a Government law officer, and the family worshipped at the Edinburgh Tron Church, on the Royal Mile. The ministers there were Moderates, not radically unorthodox, but not evangelical: they failed to give the central place in preaching to the cross of Christ; rather, their message was primarily one of good works. Robert was educated at the High School of Edinburgh, and proceeded to commence his studies at Edinburgh University aged just 14, at the time quite a normal progression. There his abilities were regarded as only above average rather than exceptional, but he possessed a particular aptitude for poetic and literary study, gifts which are certainly reflected in his subsequent sermons.

Around the time McCheyne commenced university, the family changed churches, moving to St Stephen’s congregation in the New Town, where the minister William Muir had a more evangelical reputation. This seems to reflect the increasingly earnest spiritual interest of some of Robert’s older siblings, which in turn influenced their parents. However, biographer Leen van Valen stresses that Muir is best described as a ‘middle way’ minister, not being fully Christ-centred in his message, as his extant sermons testify (Constrained by His Love, 34). Only later, after Robert became a minister, did the McCheyne family settle permanently under a robustly Scriptural ministry, that of his friend Alexander Moody Stuart, who pastored the new congregation of St Luke’s from 1835 onwards, and subsequently led the majority into the Free Church in 1843. Indeed, Adam McCheyne became the first session clerk after the Disruption.

Robert joined the congregation, but though morally upright, remained a worldly young man, enjoying parties, dancing and card-playing, occupations which he later condemned as unworthy of the Christian’s attention. He seems to have remained half-hearted in his commitment to spiritual things, until the crisis brought about by the death of his older brother David in 1831, when Robert was 18. David had become a decided believer, and frequently witnessed to Robert of the need for earnestness regarding the things of eternity. His death precipitated a spiritual crisis in which, over a period of a few months, Robert wrestled with the need to rest on Christ for salvation rather than his own upright life. He was helped to assurance by reading The Sum of Saving Knowledge, a document reportedly authored by the great Scottish Puritans David Dickson and James Durham, usually bound with the Westminster Confession of Faith, describing how to appropriate the blessings of Christ and the Covenant of Grace. The Sum is notable for its clear discussion of the Law as convicting of sin, and of the Gospel as proclaiming the Christ the solution, and this crucial division is evident in many of McCheyne’s sermons. McCheyne knew much of his own sin, especially in his diary extracts we find him repeatedly wrestling with his love of the praise of man, but he discovered what it was to cast himself on the righteousness of another.

Therefore the crucial early influence on McCheyne the developing preacher was not intellectual or moral, but spiritual, the power of the Spirit of God, and the reality of this experience remained with him throughout his life. He preached Law and Gospel with power and clarity precisely because he had personal experimental knowledge of them.

While still undergoing this spiritual crisis, Robert commenced his study of divinity at Edinburgh in preparation for the ministry of the Church of Scotland. This brought him into contact with a second great influence: the celebrated Professor of Divinity at Edinburgh, Thomas Chalmers. Chalmers was a brilliant intellect, but also a powerful spiritual influence, a Moderate minister dramatically converted to Evangelical faith, and now using the chair he had obtained to teach the next generation of Scottish ministers the theology of reconciliation by the death of Christ, received by faith in Him. McCheyne was thrilled by his lectures, but was also challenged by the personal influence of Chalmers to consider the practical side of Christian work. He and some of the other students took on visitation work in the slums of the Old Town of Edinburgh, which horrified him by the extent of the need revealed.

But there was a third crucial influence on the young student. Following his conversion experience, he no longer had an appetite for the half-hearted evangelicalism of William Muir, and he settled for the rest of his student days under a more decided ministry, that of John Bruce at the New North Church, who unlike Muir would enter the Free Church at the Disruption. Bruce was a celebrated preacher, and the Free Church Annals give a gloriously Victorian portrait of Bruce’ pulpit work:

As a preacher, Dr Bruce had a success in some respects unique. His discourses, closely read with a strong Forfarshire accent, were pervaded by a Miltonic splendour of conception and majesty of diction. Students of the greatest intellectual power were attracted by his preaching, and his ministry proved helpful to men who otherwise stood in no friendly relation to the Christian church (Annals, 106).

Two things are clear from that description. Under Bruce, McCheyne heard masterful preaching, but also experienced what a truly powerful influence the pulpit could have, even on those initially hostile to its message. There can be no doubt that his commitment to thorough, careful preparation of his sermons was rooted in the quality of ministry he heard in student days in Edinburgh.

Now let us briefly outline McCheyne’s ministry. In 1835, he was licensed to preach, and accepted an invitation to labour as an assistant to the Rev John Bonar of Larbert and Dunipace. For a year, he preached alternately in the two churches, and visited extensively throughout the parish. But a more extensive ministry was calling, and in November 1836 he was ordained and inducted to the new parish of St Peter’s, at that time covering the West end of the city of Dundee. Here he laboured in a vast parish with a large urban population, many of whom did not attend church. Even so, the gathered congregation frequently numbered more than a thousand people, a most demanding charge for a man of 23. He was methodical and diligent in his visitation, yet the quality of his sermons did not suffer, and he remained careful to prepare rigorously for the pulpit. McCheyne worked hard, but saw only limited fruit after two years of unrelenting hard labour.

By the end of 1838, he was exhausted and ill, and his doctors advised a complete rest, and he moved back to Edinburgh to stay in the family home. It was at this time that McCheyne undertook his famous journey to Palestine with Andrew Bonar and two other colleagues. Limits of space prevent us addressing that mission any further, except to note that McCheyne’s thorough knowledge of the geography of the Holy Land was an evident aid to his preaching. He returned to Dundee at the end of 1839 to find that revival had blossomed under the young supply preacher, William Chalmers Burns.

The final stage of McCheyne’s ministry was a three-year period of rich blessing and much fruit under his preaching, both in Dundee and elsewhere, even as the Ten years conflict between Church and State drew towards its climax. McCheyne signed the Solemn Engagement of 1842, and as one of the commissioners to the 1843 General Assembly, was ready then to honour that commitment in departing from an Established Church under the tyranny of the State, but the Lord had other plans. In March 1843, after months of ceaseless activity in connection with his ongoing ministry and the impending Disruption, he sickened, and after less than two weeks of growing weakness, he died on 25th March, to universal mourning. He was not yet 30 years old.

- The Sermons of McCheyne: The Flowering of a Preacher

You may be surprised to hear that opinions on the value of McCheyne’s sermons differ. I am told that my late grandmother from Lewis used to turn by preference to the sermons of Spurgeon and McCheyne for spiritual feeding, and many of the Lord’s people have found the same nourishment in these messages. But a recent biographer, David Robertson, writes in disparaging terms: ‘When one reads McCheyne’s sermons, there is not a great deal that is outstanding. His leadership gifts were strong, but had largely to mature’. Later he adds, ‘McCheyne’s sermons were not literary classics and they generally do not translate well to the printed page’, and further comments ‘His “success” cannot be gleaned from published written material, much of which will only appeal to those who are already convinced of his “sainthood”’. He goes on to propose as a question for discussion: ‘Is it worthwhile publishing sermons?’ (Awakening, 86, 137, 140). This rather suggests that he considers the value of any published sermons to be open to question, an attitude genuinely astonishing from a professedly Reformed pastor. I fear the explanation is Robertson’s view of preaching as a display of ‘leadership gifts’, rather than faithful exposition of the Word and application of it to the conscience, something sadly rare in our day. I would rather concur with the view of Maurice Roberts expressed in his preface to the reprinted volume of sermons, From the Preacher’s Heart: ‘They are the workmanship of a McCheyne, exquisite sermons in miniature, the fruits of a spiritual genius’ (11).

Most republished McCheyne sermons, including the three volumes from the Banner of Truth, are the notes of the preacher himself, and are remarkable for their fullness. There is also a published volume of notes by a hearer, entitled A Basket of Fragments, while a Banner paperback, simply called Sermons, contains a selection of both kinds, although it is remarkable how little difference there is between material from either source. This might lead one to think that McCheyne read his sermons, as some celebrated preachers of his day including Chalmers and Bruce, or that he recited them following exact memorisation, as his contemporary James Begg always did. Rather, McCheyne’s pattern was very full written preparation, but with thorough revision only, rather than memorisation, of the manuscript, and final delivery from the pulpit without any paper at all, so that his thoughts were prepared, but his language flowed freely. The result was popular preaching appreciated in his own day, but also a legacy of full-length and often very readable manuscripts.

The actual sermons fall into two categories, very typically of the age, sermons proper and expository lectures. Many Scottish preachers delivered such lectures on the Sabbath morning, and preached in the evening. The ‘lectures’ were not the detached academic presentations we associate with the term, but rather a lighter, less formal kind of sermon, usually derived from a straightforward New Testament passage, following the course of the passage for the divisions, with simple explanation and application of the text, and, crucially, usually involving consecutive exposition from week to week. McCheyne delivered extant courses of lectures from sections of Matthew, John, 1 Peter (found in NT Sermons) and Hebrews (most of the volume Sermons on Hebrews). The notes are noticeably briefer, plainer and simpler. The sermons proper were rather textual, rarely having any connection with that of the preceding week. They are much more fully prepared, including thorough explanation of the context, discussion of the meaning of key terms, illustrations and extensive application.

In terms of textual selection, McCheyne ranged over the whole Bible, more often in the New Testament than the Old, more in the epistles, especially Romans and Hebrews, than in the Gospels, although there were plenty messages from all four Evangelists. In the Old Testament, which made up about one third of his texts, his favourite books were Isaiah, Psalms and the Song of Solomon. He preached only rarely from the Pentateuch and Historical books, but often incorporated illustrations from these accounts into sermons from other passages.

In structure, McCheyne closely followed the text of the passage, seeking to divide in a natural and logical manner, which usually allows him to work progressively through the preaching portion. Introductions are succinct, and intended to focus the attention of the congregation on the content of the passage that is to be studied, and prepare for the division into heads. On one occasion, he literally just commences: ‘There are three things contained in these words’ (Sermons on Hebrews, 115). Under each head, the material is divided under further sub-heads, making the development of the preacher’s thought exceedingly clear and easy to follow. Usually the head will identify a topic in the text, which is then developed more broadly in the sub-heads, with the discussion not focussed exclusively on the passage but ranging over other texts of Scripture as appropriate. For example, on the institution of the Lord’s Supper from Matthew 26:26 (NT Sermons, 19-27), the first head is ‘Jesus took bread’, developed under sub-heads as ‘The choosing of Christ’, ‘the incarnation of Christ’; the second head ‘He blessed it’, developed as ‘He prepared a body’, ‘He anointed him’, ‘He gave him the tongue of the learned’, and ‘He held him by the hand’; third head ‘He brake’, developed similarly; fourth ‘He gave’ – the symbolism of the sacrament being opened up and shown to relate to many different texts of Scripture in a most edifying way.

From this, it will be clear that McCheyne, for all his linguistic gifts, was not an intensive expositor, a Jonathan Edwards, peeling out layer after layer of meaning from his text, burrowing into it like the surgeon with the scalpel. Rather he is a Scottish Spurgeon, a discursive preacher, treating the text like a lens through which to study the whole field of relevant Scriptural teaching. If Edwards places his texts on the dissecting table and patiently eviscerates them, McCheyne rather uses his text as a light source directed at the prism of Holy Scripture, opening up a whole spectrum of rich teaching from it. To come to practicalities, you would not use a McCheyne sermon as a substitute commentary on a text of Scripture, but could definitely use it to help ignite your passion for the subject, after the groundwork of exegesis has been laid.

Application is crucial to a McCheyne sermon, and is present throughout. Although he invariably concludes with forceful application, he also applies under each head, often bringing each head to a close with a direct and personal appeal. His application is pointed, powerful, passionate, very specific to the individual subject and yet with cumulative effect, as the evangelistic urgency in particular burns through sermon after sermon. Although McCheyne evidently loved to preach Christ to the unsaved, there is a good balance between evangelistic and pastoral messages evident in the collections, and he is just at home urging gratitude and constancy on believers as he is pressing the urgency of seeking Christ on the unbelieving. There is a clear division between messages directed at the saved and at the unsaved, and from this it may reasonably be presumed that where the sermon at one end of the Sabbath addressed the needs of the Christian, the other would be a specific, targeted evangelistic message. In general, I have found the expository lectures, probably delivered on Sabbath mornings, to be more often addressed to the believer – simple, homely, encouraging messages of Christian teaching – and the sermons to be evangelistic, although there are many exceptions to this rule. McCheyne did not flinch from directness, for all his youth, and his application is always addressed to ‘you’.

His style is simple, yet full of rhetorical energy: questions, challenges, objections anticipated and answered robustly, relevant texts quoted with conviction and authority. In terms of illustration, he never uses ‘stories’; rather, he deploys succinct but potent word-pictures, often Biblical images clothed in fresh language. Anything like joking or flippancy is utterly excluded – the tone is sober, earnest, urgent throughout, illustration serving the purpose of the preaching, not distracting from it. Consider his description of the new convert’s first experience of falling into sin:

You may have seen some bird of noble plumage rising from the earth on swift, careering wing; he leaves behind him the dull clods of the earth and soars to heaven as if it were his native element, when suddenly the whizzing bullet pierces his feathered side. On the instant all his noble energy is gone, he droops the head and covers the wing and whirling, falls from his dizzy height, down to the earth again. Just so the believer is exalted to heaven by the sweet peace wherewith the sprinkled blood has filled his soul, breathing a purer atmosphere, beginning now to think that heaven is gained; but suddenly the arrow of the Wicked One pierces his side and he falls. Ah! How low, who can tell? Who can tell the misery of the believer’s first sin? (OT Sermons, 141).

Or for a specifically Biblical image, hear this description of the believer’s hope:

The hope that makes not ashamed, the anchor of the soul, sure and steadfast, that enters within the veil, that is riveted on the golden shore of a blessed eternity (NT Sermons, 114).

It is thrilling, potent language: ‘riveted on the golden shore of a blessed eternity’, all the poetic gifts of the young student of literature harnessed to the work of the Kingdom of Christ!

What, fundamentally, was special about McCheyne the preacher? I think what lent him his power was the reality of experience that underlay his sermons. He was experimental, in the best sense, like the Puritans, the Covenanters, like the Apostles themselves, he spoke of what he knew. This functioned with regard to the reality of sin, for example on the danger of the sin of adultery:

Many may be ready to say, ‘Is thy servant a dog, that he should do this thing? But those of you who know the hell that is within will tremblingly keep near to God and say, Lead me not into temptation. Given opportunity on the one hand, and Satan tempting on the other, and the grace of God at neither, where should you and I be? (NT Sermons, 307).

Or on the believer who is betrayed into worldly company:

From the beginning to the end of the feast, he hears nothing but worldly conversation. All around him people are taking though what they shall eat or what they shall drink. The name of the Saviour is not once mentioned. To introduce it would be like bringing in a poisonous serpent, from which every one would shrink back with horror. The believer sits silent, and is half ashamed of Christ. He is ashamed to show that he is a Christian. And when he comes home at night, what wonder if prayer and the Word be all distasteful to him, and he has lost all sense of safety (NT Sermons, 185).

This is experimental teaching that reflects real life, real sin. It is searingly honest. But there is another side to this too: hear the experimental comfort of these words to the believer anxious over the reality of sin:

Even Christians are filled with shame, when they look only on themselves and what they have been. But when they look to Christ, their shame is forgotten. There are two reasons:

- Their sins, they see, are fully accounted for in the sufferings of Christ; more fully than if they themselves had suffered eternally.

- They see that they are righteous in God’s sight, that God loves them, how can they be ashamed anymore? They have ‘no more conscience of sins’ (Heb 10:2), like those in Heaven who have washed their robes in the blood of the Lamb (Rev 7:14). They remember their sins but they are not ashamed. Even here, insofar as you live by faith, you may live without shame (OT Sermons, 158).

This teaching is experimental in the best sense, rooted and grounded in the experience of grace.

The historian of preaching, William Garden Blaikie, summed up the uniqueness of McCheyne’s pulpit work as follows:

‘The new element he brought into the pulpit, or rather which he revived and used so much that it appeared new, was winsomeness. It was an almost feminine quality. A pity that turned many of his sermons into elegiac poems, thrilled his heart, and by the power of the Spirit imparted the thrill to many souls’ (Blaikie, Preachers, 295).

He had the warmth of sympathy of one who knew what it was to walk in life trusting in morality, called a Christian but without a real change. He knew the value of grace, the change it brings, and therefore he spoke with experimental warmth, love and passion, which gave to his message a winning, winsome quality that so touched those who heard him, that under the sovereign influence of the Spirit, it was the means of salvation to many.

To illustrate my discussion of McCheyne’s preaching, I have chosen an exemplary sermon, an Old Testament evangelistic message, on the ‘Cities of Refuge’ from Joshua 20 (OT Sermons, 9-18). The message commences with a lively introduction expressing in dramatic terms the Israelite’s anticipation of Christ through the various types:

When he stood beside the smitten rock and saw the waters gush out and follow[ed] them day by day, a mighty river running through a desert, he thought with joy of the Saviour who is ‘as rivers of water in a dry place’.

So the manna, the pillar-cloud, the serpent raised, all lead to the crucial assertion, which determines the whole course of the message: ‘The cities of refuge were intended to set forth Jesus’. He then gives his first head as follows: ‘They were like Christ in situation’, sub-divided ‘in nearness’ and ‘in being conspicuous’, showing how these characteristics are reflected in Christ. The latter is especially graphic in describing the geography of the six cities, emphasising their visibility, leading to the thrilling passage:

It seems probable that there was scarcely a place in the land from which you could not spy one of these refuge cities. So that, when the believing Israelite went out to meditate like Isaac at eventide, when he saw the sun gleaming on the fruitful top of Gerizim, or the white walls of Hebron, or the far off tower of Bezer in the wilderness, or the embowered dwellings of Ramoth-gilead, or the snow on the high hill of Bashan, every one seemed a witness for Christ. Every one had a tongue and said ‘Come unto me, and I will give you rest’.

This leads him to wonderfully direct application:

This shows the heart of God toward you. He wants you to come to a lifted-up Christ on the cross and on the throne. Christ is a lifted-up Saviour in the preached word, that any sinner may flee to Him and be safe. Oh come to a lifted-up Christ!

The second head is ‘They were like Christ in ease of access’, developed in the ‘roads’, the ‘waymarks’ and the ‘open gates’, each sub-point being individually applied and pressed with tremendous cumulative force. The third head is ‘They were like Christ in the safety found there’, developed in the ‘Safety obtained on entering’, ‘Safety for Jew and Stranger’, and ‘Instruction to be found there’ – that is, the role of these cities as residences for the Levites. His closing application is a direct challenge to two specific groups: first to awakened persons seeking Christ only with slackness, whom he compares to fleers from the avenger of blood loitering on the way, still outside the city gates. The final challenge is to believers themselves, not forgotten amidst a focussed, specific evangelistic message, warning them briefly in closing to abide within the city, to cleave to Christ.

Throughout, the sermon is characterised by vivid language and passion in commending Christ, and in this sense compares closely in character and quality with the finest sermons of C. H. Spurgeon. The clarity with which the Old Testament is read as Christian Scripture, the vigour with which the faith of the Old Tetsament saints is shown to rest on Christ, the directness of the type in its prophetic illustration of the salvation of Christ, all serve to make this a powerful, memorable discourse, evangelistic, challenging, and yet rich, edifying reading for the believer. David Robertson may disparage them, but McCheyne’s written sermons still speak to us today.

III. The Preaching of McCheyne: The Lessons from a Preacher

I intend to bring eight short but important lessons, both positive and negative, from the life of McCheyne. I trust I need scarcely add that as the youngest of preachers I apply these first of all to myself, and have much to do yet to put them into practice.

- He Challenges You to Positivity regarding the Young

McCheyne lived and died a young man. In terms of the FCC, at 29 he could still have been a regular at Arbroath. And yet see the depth of understanding, the spiritual maturity, the seasoned understanding of the crests and troughs of Christian experience revealed throughout these sermons. When you remember that some messages are dated as early as 1836, when he was just 23, these books are a real challenge to those of you whose instinctive prescription to any young man wrestling with a call to devote his life to preaching the Gospel is to ‘get more life experience’. If McCheyne had followed that counsel, he might never have preached at all. Equally, they are a rebuke to you whose expectations of young people are little more than that they keep quiet and listen. Certainly let all of us be teachable, the young above all, but equally let pastors especially cherish high expectations of their young members, that they will advance rapidly in godliness, will develop and demonstrate an earnest and intelligent commitment to the principles of Scripture and of Reformed theology, and will edify in turn the rest of the congregation.

- He Challenges You to Diligence in Pulpit Preparation

These manuscripts were not composed for publication; rather they are merely standard preparation for regular pulpit duties from week to week. How thoroughly and carefully McCheyne prepared to preach the Word of God! What wonder if these full, thoughtful, meticulous manuscripts laid a foundation for preaching that thrilled and excited congregations? What wonder if scrappy notes, key words that just rely on the inspiration of the moment for the language to clarify and explain, familiar and well-worn lines of application, tend to elicit more yawns than active response from congregations? And remember that when he came to the pulpit, there was no manuscript needed at all, just an open Bible and the eyes of his hearers.

- He Challenges You to Prepare Exclusively Evangelistic Sermons

It is easy to fall into the trap of imagining that the really great sermons are those that delve into the profoundest depths of Christian doctrine, or that brim with clever insights into obscure passages of Scripture. But remember Lloyd-Jones’ observation, that the hardest preaching of all is preaching to win the lost to Christ. Here is McCheyne, the finest of preachers, and yet easily half his sermons are addressed specifically to the unbelieving, with the simple purpose of urgently pressing upon them the way of salvation in Jesus. In exhibiting that task done, continually, faithfully, and yet always with freshness and vigour, McCheyne exhibits for us the true Christian preacher. Never let yourself get sidetracked from the regular work of the Kingdom by anything else, however worthy. Be as Paul, reasoning ‘of righteousness, temperance, and judgment to come’. If we are known for nothing else as preachers, let us strive to be known as those who continually, earnestly, lovingly, set forth salvation in Christ Jesus, and press men towards it.

- He Challenges You to Passion in Preaching Eternal Realities

McCheyne could not be casual in setting forth the danger of remaining outside Christ. He spoke with unmistakeable, at times even uncomfortable boldness and frankness of the horrors of eternal wrath against sin:

In heaven, we shall see the wrath of God poured out upon the Christless; we shall see their pale, dismal faces, we shall hear their sad cries and the gnashing of their teeth; we shall see the smoke of their torment ascending up before God forever. Oh, how shall we praise God for His electing love that chose us to salvation! How all believers shall praise Christ for his redeeming love, for enduring such pains in our stead! (NT Sermons, 193).

Such a subject was real to McCheyne, and thus was made real in the preaching to his hearers, to an extent tragically rare in our day. Equally, the joys of Heaven, the glory of Christ, and the eternal love of God were all profoundly real in his handling. Perhaps if you and I preached these truths with more conviction, more passion, we would see more fruit.

- He Challenges You to Preach from Experience of Christ

Perhaps this lesson must stand above all. McCheyne’s sermons are thoroughly experimental, grounded in real experience, and especially in experience of knowing Christ as Saviour and Lord. This does not require continual reference to ‘me, myself and I’; rather, it calls for preaching that has felt that of which it speaks. Hear these words and consider if they could come with any conviction without a foundation in experience, on union with Christ:

Oh! What infinite honour that the Son of God should leave the bosom of the Father and propose so close, so mysterious, so blessed a union as this, with base and sinful worms, ‘whose cottages are of clay, and who are crushed before the moth’. Oh! If there is one thing more wonderful in the whole world than this, it is that any one of us, base-born worms of a day, should refuse a union of such unspeakable grace. (NT Sermons, 3).

See how the certainty that can only arise from real personal experience gives weight and point to the message.

- He Challenges You to a Sensible Biblical Balance in Preaching

McCheyne had some singular views. He was fascinated by eschatology, and held like the Bonars to a form of premillenialism influenced by Edward Irving. He was passionately concerned for the evangelism of the Jews, was fiercely opposed to Moderatism in all its guises, and held strongly to the Establishment Principle. Yet it is striking how little that is controversial finds a place in his preaching. His primary concern is emphatically with dealing with the souls of men, and all else is secondary. His preaching portions show a reasonable balance throughout Scripture, if anything tending to avoid apocalyptic books like Daniel and Revelation, except for his famous series on the Seven Churches of Asia. You all know that there are preachers with a tendency to have bees in the bonnet, pet subjects always good for a few minutes of filler when the sermon is not flowing. Romanism is all too often used in this way, a safe subject for a good rant, and such preachers find Jesuits and Illuminati lurking behind the most innocuous of texts. And so the congregation settle back for a familiar tirade against papists, sodomites, abortionists, textual critics, and other groups notable chiefly for their absence from the gathered congregation. In the light of McCheyne’s example, such stuff should be seen for what it is, a pointless abuse of precious pulpit time. Address what is relevant to the subject, and address it when you something worthwhile to say.

Now for the negative lessons:

- He Challenges You to Preach as You are Gifted by God

McCheyne’s sermons are not consistent in their quality. His sermons proper are good, sometimes truly wonderful; but his expository lectures are overall quite average in their content. Though full of solid Christian teaching, they are without real sparkle, vigour or striking insight. Indeed the change in NT Sermons from the textual sermons of the first half, to the long series of lectures on 1 Peter is a startling change of pace and of quality. The explanation is patently obvious: McCheyne had no real proficiency in consecutive exposition. He is a Spurgeon rather than a Lloyd-Jones, a discursive rather than an expository preacher, a devotee of the telescope rather than the microscope. Going through 1 Peter, he treats every chosen portion as a distinct unit, conveys no sense of ongoing themes, or of a developing argument, and consequently is very hit-and-miss. On some passages, as on 2:9, he gains real traction, and preaches powerfully; but others are quite ordinary messages, such as any competent preacher might produce. Some of the loveliest passages have no relevance to 1 Peter, and merely use the text as a springboard from which to discuss some aspect of the whole field of Scripture, such as on 2:3, ‘if so be ye have tasted that the Lord is gracious’, where he heads straight into showing that Scripture compares the exercise of faith to each of the five sense in turn, which he uses as divisions. That is not wrong, but neither is it conducive to a consistent quality of consecutive exposition. The lectures on Hebrews are better, but I suspect only because the subject matter so passionately interested McCheyne, so that many portions inspire good individual messages. Play to your own strengths as a preacher, and do not fall into the trap of boring your congregation by trying to preach long expository series if God equipped you rather to be a good textual preacher.

- He Challenges You to Safeguard Your Own Health

McCheyne worked himself into an early grave. Even in 1843, fit young men of 29 without any chronic illness did not routinely expire. From his earliest days of ministry, he made it is his practice never to refuse an invitation to preach. Even Bonar, the gentlest of biographers, acknowledges that McCheyne was far to ready to leave his congregation to fulfil an engagement, and in the last year of his life we see him twice visiting England (then a long, wearing journey by horse-drawn carriage) on preaching tours, and visiting parishes all over rural Aberdeenshire to prepare congregations for the coming Disruption. He reportedly preached six times in two days, or on another occasion twenty-seven times in twenty-four days. By the last year of his life his musical, melodious voice was hoarse and cracked, his natural colour was gone, his frame shrunken, his energy dissipated. What might McCheyne have achieved had he lived a normal span? He could well have been a Scottish Spurgeon, preaching with freshness and vigour year after year, decade after decade, winning multitudes to Christ. He could have been one who discipled a whole generation of young believers in holiness of living and purity of doctrine. It is startling to remember that McCheyne’s personal friend Rev William Aitken of Carlops was one of the Free Church of Scotland ministers who stood bravely outside the Union of 1900, and lived on into the age of motor car and telephone, dying eventually in 1925. Never imagine that it is a waste of your time to give thought to healthy eating, regular exercise, and periodic holidays.

Conclusion: McCheyne and the Literature

The one essential biography of McCheyne is the Memoir by Andrew Bonar, an Evangelical classic, and stirring heart-warming reading. If you are not challenged by the passion and drive for holiness of the young divinity student as seen in his diary extracts, if you are not thrilled as the weary pastor returns from the Holy Land, to find the Spirit rained down in revival power upon his congregation, if you are not moved as the bereft congregation gathers to weep together in their church building on a Saturday evening, mourning the passing of their young shepherd, you have no soul. The best modern biography is Leen Van Valen’s Constrained by His Love, which has been translated from the Dutch. It is very detailed and lengthy, but is fully in sympathy with M’Cheyne’s evangelical passion. David Robertson’s Awakening is predictably opinionated, but is a good concise account for all that, drawing out some useful challenges for our own day from McCheyne’s example. I understand Mr Robertson has now abandoned his attempt to complete a PhD on McCheyne, but there is one older thesis already, by David Yeaworth (Edinburgh University, 1957), which is freely available online, and contains useful material.

Of the three volumes of recently published sermons, all are worthy, but I particularly recommend New Testament Sermons to purchase and to read, as it contains some of M’Cheyne’s preaching at his absolute best, as well as a good representative sampling of his expository lecturing on 1 Peter. For the keen reader, I would further recommend From the Preacher’s Heart, which was originally published in the nineteenth century under the rather grim title, Additional Remains of R M McCheyne. It contains a large selection of representative sermons, including some real gems. But the full volume of Memoir and Remains contains a very full sample of all McCheyne’s different writing: poetry, tracts, letters, lectures, sermons and the famous Bible Reading Plan. This is the place to begin experiencing McCheyne!

Leave a Reply